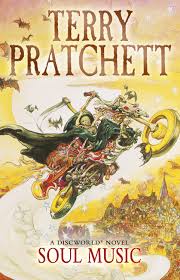

There are a precious few of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels that I have not yet read, and I am clinging to them covetously, putting off reading them because all too soon there will be no more additions to the Discworld library. Sir Terry is still alive and kicking and churning out novels, but he is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease—that he remains this prolific is nothing short of heroic. As much as we don’t want to acknowledge it, Discworld devotees know that sooner or later there will be no more novels forthcoming.

There are a precious few of Terry Pratchett’s Discworld novels that I have not yet read, and I am clinging to them covetously, putting off reading them because all too soon there will be no more additions to the Discworld library. Sir Terry is still alive and kicking and churning out novels, but he is suffering from Alzheimer’s disease—that he remains this prolific is nothing short of heroic. As much as we don’t want to acknowledge it, Discworld devotees know that sooner or later there will be no more novels forthcoming.

Raising Steam is the fortieth Discworld novel (the thirty-sixth if you don’t count the young adult novels), and is still currently in hardcover. I had been putting off buying it, waiting for the paperback but also possibly adding it to the small pile of Discworld novels I was resisting reading. But at Slayage I discovered a fellow Discworld devotee, my new friend Dale whose blog I quoted in my previous post. She had just finished Raising Steam and gifted me with her copy, on the condition that I told her what I thought of it when I was done.

Well … here I go. Fair warning: this post is not so much a review of Raising Steam as it is a working-through of thoughts I have had about Pratchett’s writing for some time, which his most recent novel has managed to bring into something resembling sharp relief.

Also fair warning: spoilers.

*

Raising Steam brings the railway to Discworld: it begins as a young engineer named Dick Simnel continues with the experiments with steam that had killed his father, and ends with the new railway connecting the city of Ankh-Morpork—a center of Discworld commerce and culture—with far-flung Uberwald, in the process facilitating a mission of speedy diplomacy that restores the progressive Low King of the dwarfs to his usurped throne … which itself allows for a seismic change to dwarf society.

I’ve subtitled this review “Modernity Comes to Discworld,” but anyone who is more than just a casual reader of Sir Terry’s novels knows that that is more than just a little disingenuous. The Discworld is a fantasy world through and through, and as such displays all of the conventions of fantasy we have come to expect and then some: dwarfs, trolls, goblins, wizards, witches, gods, magic, castles, quests, prophecies, dragons, supernatural plots and conspiracies, and so forth. But in a variety of ways, Pratchett’s novels only present the façade of fantasy. If we define fantasy fiction as a genre that anchors its magical and supernatural elements in an identifiably medieval or at least premodern setting (as George R.R. Martin has said on several occasions, fantasy and historical fiction are “sisters beneath the skin”), Pratchett arguably performs a constant bait-and-switch insofar as that the Discworld and its denizens—or at least those denizens who star in the novels—don’t exactly embody a Tolkienesque sensibility. “Modernity” has been creeping into the Discworld landscape almost from the start.

Even so, the introduction of the steam engine and the railway is still somewhat jarring, for the simple reason that it is perhaps the single greatest symbol of modernity and industrialization. I have written elsewhere that, in the Harry Potter novels, the Hogwarts Express is a peculiarly potent presence in that it functions as a sort of representative time machine—a nineteenth-century bridge between postmodern London and medieval England. In Raising Steam that trajectory is reversed as Dick Simnel’s newfangled gadget hurtles, along with its many enthusiastic passengers, into Discworld’s uncharted future.

Considering Pratchett’s incremental modernization of Discworld, which I’ll discuss below, it is difficult not to read Raising Steam and the massive paradigm shift the locomotive represents as the culmination of a life’s work. As mentioned about, Sir Terry was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s in 2007. Mercifully, it has been a mild case, and he does not appear to have missed a step in his writing since then (though now he no longer types his own work, but has to dictate and otherwise work an assistant to get the words on the page). However, his fans wait in dread for the inevitable. Only a few days ago, a friend pointed me to an article in The Guardian, which reports that Sir Terry has had to cancel his appearance at the International Discworld Convention because of his Alzheimers, saying sadly that “the Embuggerance is finally catching up with me.”

Is the railway a parting gift to Discworld? Is he officially ushering it into the modern age while he still can? It might seem odd, in a fantasy series, to impose modern technology on the fantasy world: certainly, Tolkien would have been aghast to have steel rails and belching locomotives cutting a swath through the Shire (as indeed, the dystopian Shire to which the hobbits return was precisely an anti-industrial polemic). But Pratchett has a very different relationship to fantasy than did Tolkien, or really even most people writing fantasy today. The nostalgic quality that inflects much of the genre is largely absent in Discworld—rather, Sir Terry uses fantasy as a comedic means to explore the relationship between narrative’s folkloric tendencies and the exigencies of the modern world.

*

The Discworld novels started in 1983 with The Colour of Magic, which was followed by The Light Fantastic. Both of these novels were essentially parodies of fantasy as a genre, with comically outsized heroes, improbable and illogical encounters, and bizarre plot twists as befit characters traveling across a magical landscape. But as Discworld evolved and Sir Terry added more and more stories to the series (he published fifteen Discworld novels between 1983 and 1993), Discworld and its inhabitants took on form and substance that, while unfailingly funny, became less about parodying fantasy and more about employing fantasy to articulate a markedly humanist and pragmatic world view.

The Discworld novels started in 1983 with The Colour of Magic, which was followed by The Light Fantastic. Both of these novels were essentially parodies of fantasy as a genre, with comically outsized heroes, improbable and illogical encounters, and bizarre plot twists as befit characters traveling across a magical landscape. But as Discworld evolved and Sir Terry added more and more stories to the series (he published fifteen Discworld novels between 1983 and 1993), Discworld and its inhabitants took on form and substance that, while unfailingly funny, became less about parodying fantasy and more about employing fantasy to articulate a markedly humanist and pragmatic world view.

Pratchett himself has always been an outspoken humanist, perhaps most famously in his oft-repeated pronouncement that “I’d rather be a rising ape than a falling angel.” In that sentiment one glimpses something essential to the Discworld ethos: the valorization of human potential over divine intervention, and the figuration of people (which in the case of Discworld is not just humans but dwarfs, trolls, vampires, and so forth) as progressive and emergent rather than fallen, postlapsarian beings. Pratchett’s sensibility, not to put too fine a point on it, is an eminently sensible one, which sees more wonder in the simple fact that beings evolved from monkeys invented streetlamps than in any ostensible divine origin:

I find it far more interesting … that a bunch of monkeys got down off the trees and stopped arguing long enough to build this … to build that, to build everything. And we’re monkeys—our heritage is, in times of difficulty, climb a tree and throw shit at other trees. That’s so much more interesting than being fallen angels … Within the story of evolution is a story far more interesting than any in the Bible. It teaches us amazing things. That stars are not important. There’s nothing interesting about stars. Streetlamps are very important, because they’re so rare … as far as we know, there’s only a few million of them in the universe. And they were built by monkeys! Who came up with philosophy, and gods! And this is so much more interesting, it is so much more right. Admittedly, we err, such as when we made Tony Blair prime minister. But given where we started from … we actually haven’t done that badly. And I would much rather be a rising ape than a falling angel.

I disagree with him on the unimportance or tedium of stars, but his point is well taken (and, really, is just a rhetorical flourish). The above is from a talk he gave for The Guardian, the relevant part of which can be viewed on YouTube:

The Discworld novels articulate and expand on the various facets and implications of such sentiments. His assertion that “In my religion, the building of a telescope is the building of a cathedral” finds numerous corollaries, as he introduces various modern phenomena into Discworld in parodic fashion—though not to parody fantasy as in his first two novels, but rather to use fantasy as a means to parody our own real-world foibles. In Moving Pictures (1990) and Soul Music (1994), cinema and rock and roll, respectively, make appearances on the Discworld scene, in both cases facilitated by quasi-magical circumstances to emerge and reach critical mass before disappearing as the magical framework collapses. But where these end up as one-offs in Discworld, the last fifteen years or so (or, to measure time in Pratchett productivity, sixteen Discworld novels) has seen a number of modern incursions into Sir Terry’s fantasy world taking root and expanding.

The Discworld novels articulate and expand on the various facets and implications of such sentiments. His assertion that “In my religion, the building of a telescope is the building of a cathedral” finds numerous corollaries, as he introduces various modern phenomena into Discworld in parodic fashion—though not to parody fantasy as in his first two novels, but rather to use fantasy as a means to parody our own real-world foibles. In Moving Pictures (1990) and Soul Music (1994), cinema and rock and roll, respectively, make appearances on the Discworld scene, in both cases facilitated by quasi-magical circumstances to emerge and reach critical mass before disappearing as the magical framework collapses. But where these end up as one-offs in Discworld, the last fifteen years or so (or, to measure time in Pratchett productivity, sixteen Discworld novels) has seen a number of modern incursions into Sir Terry’s fantasy world taking root and expanding.

Perhaps first and foremost among these is the network of “clacks towers,” which first appears in The Fifth Elephant (1999). The clacks towers are the Discworld analogue to the telegraph: lines of towers in visual range of each other, which relay messages through a series of semaphore-type codes, and which (by the time we get to Raising Steam) run the length and breadth of Discworld and have become integral to both politics and commerce. In The Truth (2000), the printing press arrives in the city of Ankh-Morpork, which gives rise to the invention of the newspaper and the profession of journalism. In Going Postal (2004), Ankh-Morpork establishes the modern postal system; and in Making Money (2007), modern banking and coinage.

It is important to note here that as our image of Discworld evolves over numerous novels, it becomes clear that the city of Ankh-Morpork—center of commerce, polyglot metropolis, and emigration destination for pretty much all races and species in Discworld—comes to emblematize Sir Terry’s humanistic ethos. It is a place where peoples from all over Discworld, both humans of all stripes and species such as dwarfs of trolls, come to make new lives, to earn money to send home, or to flee their homelands. It is not, to be clear, a nice place—it is dirty, overpopulated, violent, capricious, and fickle—but in being distinctively un-utopian (without being actually dystopian), it depicts the inescapable messiness of the humanist project. Some of the most profound conflicts in Sir Terry’s novels occur when individuals or groups of great power (magical or otherwise) attempt to clean up the messiness of humanity and impose a “clean,” neat utopian order—such as happens in Reaper Man (1991), Small Gods (1992), Hogfather (1996), The Truth (2000), Thief of Time (2001), and Night Watch (2002). “The moment you start measuring people,” reflects Sam Vimes in Night Watch, “sooner or later, people don’t measure up.” The imposition of an autocratic, absolute external logic is anathema to Sir Terry. One of his key recurring characters is the Patrician of Ankh-Morpork, Lord Havelock Vetinari. Vetinari is, for all intents and purposes, the Platonic ideal of the benevolent dictator, a beautifully Machiavellian character in the truest sense of the word insofar as his primary concern is not the maintenance of his own power but the welfare of his city. Though he is a self-described tyrant and at times behaves in a tyrannical manner (certainly, his enemies never fare well), he proceeds from the foundational understanding that a healthy society is one in which individuals must have the freedom to make their own choices, and that the role of government was to make certain no one faction of society’s choices took precedence over any other’s.

(An attitude that pervades many parts of Discworld, even those more specifically medieval and premodern than Ankh-Morpork. The Kingdom of Lancre, for example, the most obviously medieval European region of Discworld, resists any attempt at democratization, but their attitude to kings is such that imposing an absolute monarchy would be monumentally difficult:

The people of Lancre wouldn’t dream of living in anything other than a monarchy. They’d done so for thousands of years and knew that it worked. But they’d also found that it didn’t do to pay too much attention to what the king wanted, because there was bound to be another king along in forty years or so and he’d be certain to want something different and so they’d have gone to all that trouble for nothing. In the meantime, his job as they saw it was to mostly stay in the palace, practice the waving, have enough sense to face the right way on coins and let them get on with the plowing, sowing, growing and harvesting. It was, as they saw it, a social contract. They did what they always did, and he let them. (Carpe Jugulum)

The Discworld novels are marked by this sort of pragmatism, pragmatism that is both the commonsensical and quotidian variety, and the philosophical kind.)

Ankh-Morpork sits in the midst of an archipelago of fantasy analogues to different real-world premodern societies, from Lancre, to Uberwald’s gothic medieval, to Djelibeybi’s re-imagination of ancient Egypt, Klatch’s Middle-East, the Agatean Empire’s dynastic China, or the city-state of Ephebe’s version of ancient Athens. Ankh-Morpork exerts a gravitational pull on all these places and draws the denizens of otherwise isolated and xenophobic societies into direct and profitable contact with one another. And it is therefore unsurprising that all of the elements of modernity that Pratchett introduces into Discworld either emerge in Ankh-Morpork or are refined (and monetized) there.

The steam engine and railway in Raising Steam are no exception in this respect. The only real difference is that in this novel there is an awful lot more musing on the nature of progress and innovation. Moist von Lipwig, hero of Going Postal and Making Money, whom Vetinari once again ropes into managing a new phenomenon for the benefit of Ankh-Morpork, takes to the task with far less reluctance than with the city’s post office, bank, and mint. The former con man and scoundrel sees all too clearly the railway’s potential, and frequently pauses to reflect on the nature of progress, in both its destructive and beneficial effects in which old orders crumble but create new possibilities. Even Lord Vetinari is more given to philosophical reflection than usual, at first looking suspiciously at this new technology but quickly resigning himself to its inevitability (with Moist looking out for the city’s interests, however).

Curious, the Patrician thought … that people in Ankh-Morpork professed not to like change while at the same time fixating on every new entertainment and diversion that came their way. There was nothing the mob liked better than novelty. Lord Vetinari sighed again. Did they actually think? These days everybody used the clacks, even little old ladies who used it to send him clacks messages complaining about these newfangled ideas, totally missing the irony. And in this doleful mood he ventured to wonder if they ever thought back to when things were just old-fangled or not fangled at all as against the modern day when fangled had reached its apogee. Fangling was indeed, he thought, here to stay.

The conflict at the center of Raising Steam is not about the development of the railway per se, but with a power struggle occurring in dwarf society. Of all the races and species inhabiting Discworld, dwarfs are (after humans) the most complexly imagined. Two previous novels, The Fifth Elephant (1999) and Thud! (2007) looked closely at the history of dwarfish culture, its customs and traditions, and the faultlines that have always run through it. There has always been a divide among dwarfs between the forces of tradition and those of progress, between those purists who wish to hew to an authentic, ur-dwarfishness, and those who leave their homeland and its mines and (frequently) settle in Ankh-Morpork.

At its heart, Raising Steam is less about the modernizing force of technology than the confrontation between a fanatical devotion to tradition and the exigencies of a rapidly changing world. One thing we learned in The Fifth Elephant was that male and female dwarfs look more or less identical, and only acknowledge themselves as male outside the privacy of marriage (which, as Pratchett notes, makes courtship a delicate affair). But in The Fifth Elephant, female dwarfs in Ankh-Morpork have started to identify as female, something veritably heretical in their homeland of Uberwald. The Fifth Elephant was about the coronation of a progressive king; in Thud!, the dwarfs negotiate a peace treaty with their traditional enemies, the trolls. In both cases, these crucial events were quietly orchestrated by Lord Vetinari through his proxy Samuel Vimes, commander of the City Watch.

In Raising Steam, a schism among the absolutist dwarfs—the “grags” or “delvers” as they are known—leads not just to a coup d’etat, but also to terroristic attacks on the clacks network and the embryonic railway, symbols of change and progress that the purist delvers cannot abide. I won’t make any claim that the novel is subtle on this front: the delvers very obviously represent fundamentalist and evangelical factions in contemporary culture, something made painfully obvious by the fact that delvers will only emerge from below ground when clad in heavy black robes that hide their faces.

This lack of subtlety is part of the reason why this novel feels like Pratchett hurrying Discworld out of its medieval trappings and firmly into the modern world. The reinstated dwarfish king, Rhys Rhysson, lays it out for his fundamentalist foes in no uncertain terms:

[I]t is your kind that makes dwarfs small, wrapped up in themselves: declaring that any tiny change in what is thought to be a dwarf is somehow sacrilege. I can remember the days when even talking to a human was forbidden by idiots such as you. And now you have to understand it’s not about dwarfs, or the humans, or the trolls, it’s about the people, and that’s where the troublesome Lord Vetinari wins the game. In Ankh-Morpork you can be whatever you want to be and sometimes people laugh and sometimes they clap, and mostly and beautifully, they don’t really care.

Rhys then goes on to truly shake dwarf society to its core by revealing that he is not, in fact, their king at all but their queen—and defiantly rejects the title of king, saying that from that moment on, dwarfs will no longer be required to hide or deny their gender.

All of which was made possible, of course, by the construction of the railway: anticipating problems in Uberwald (where the dwarfs’ Low Kingdom resides), Vetinari orders Moist von Lipwig to make certain the railway will run the entire distance (which Moist protests is impossible in the allotted time—but Vetinari exercises the tyrant’s prerogative and demands that it be done). Of course, though it is touch and go, he succeeds—and the timely return of Queen Rhys allows her to reclaim the throne and make her game-changing announcement.

I can’t say that Raising Steam is among the best Discworld novels … though it avoids the narrative incoherence that marked Snuff (2012) and Unseen Academicals (2010), as I’ve observed, it is markedly unsubtle in its themes and execution—though thankfully in very interesting ways that have helped clarify some of my thinking about the Discworld series. There is an unmistakably wistful tone that makes me wonder if we’ll see Ankh-Morpork and the geopolitics of Discworld depicted again (Pratchett’s apology to the Discworld Convention states that he has a new Tiffany Aching novel in process, but I find that the YA Discworld novels lack the broader sense of the world at large). The novel’s final word is given to Lord Ventinari, who muses, “all that anyone can say now is: What next? What little thing will change the world because the tinkers carried on tinkering?”

What indeed.