I’ve taught the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft twice now: first in a second-year introduction to science fiction and fantasy, in which I paired up “classic” texts with more contemporary ones (Lovecraft I counterpoised with short fiction by China Miéville), and more extensively in a fourth-year seminar I called “The American Weird.” In the latter, we spent three weeks of a twelve-week semester looking specifically at Lovecraft’s short fiction, as well as his novella At the Mountains of Madness. And then we looked at authors who have been influenced by Lovecraft (Stephen King, for example), or who more specifically engage critically with Lovecraft’s tropes, preoccupations, and, importantly, his racism. One of the latter texts was a novella by Victor LaValle, The Ballad of Black Tom, which is a retelling of Lovecraft’s hella racist story (even for him) “The Horror at Red Hook,” from the perspective of a Black protagonist.

I’ve taught the fiction of H.P. Lovecraft twice now: first in a second-year introduction to science fiction and fantasy, in which I paired up “classic” texts with more contemporary ones (Lovecraft I counterpoised with short fiction by China Miéville), and more extensively in a fourth-year seminar I called “The American Weird.” In the latter, we spent three weeks of a twelve-week semester looking specifically at Lovecraft’s short fiction, as well as his novella At the Mountains of Madness. And then we looked at authors who have been influenced by Lovecraft (Stephen King, for example), or who more specifically engage critically with Lovecraft’s tropes, preoccupations, and, importantly, his racism. One of the latter texts was a novella by Victor LaValle, The Ballad of Black Tom, which is a retelling of Lovecraft’s hella racist story (even for him) “The Horror at Red Hook,” from the perspective of a Black protagonist.

One of the other texts in the latter category was Matt Ruff’s novel Lovecraft Country.

Lovecraft Country was easily a class favourite—which was something of a relief, as it was easily my favourite, and indeed one of the reasons I’d conceived of the course in the first place. So when HBO announced that Jordan Peele would be producing a series based on the novel, I was about as excited as I’d been ten years ago about Game of Thrones. The fact that one of the main characters was slated to be played by Michael K. Williams, aka Omar from The Wire, was just icing on the cake.

Lovecraft Country was easily a class favourite—which was something of a relief, as it was easily my favourite, and indeed one of the reasons I’d conceived of the course in the first place. So when HBO announced that Jordan Peele would be producing a series based on the novel, I was about as excited as I’d been ten years ago about Game of Thrones. The fact that one of the main characters was slated to be played by Michael K. Williams, aka Omar from The Wire, was just icing on the cake.

And after what seemed an interminable interlude, the series premiered this week.

I’m mulling whether I want to do episode-by-episode posts, á là my GoT posts with Nikki (except sans Nikki, unless she wants in). This may or may not happen. But I cannot let the first episode go by without airing my thoughts.

However … I won’t be talking about the first episode in this post. I’d originally thought I should have a brief little primer on H.P. Lovecraft, so as to better get into what Lovecraft Country is doing.

But, as anyone who knows me will tell you, I don’t do brief. And so I’ll be doing a second post in a day or two on the episode—this one is a more in-depth discussion of Lovecraft than I’d intended.

Lovecraft, it needs to be said, is something of an odd literary figure, insofar as he was an objectively terrible writer, both in terms of his prose and his storytelling, who ended up exerting an outsized influence on horror and its overlapping genres of science fiction and fantasy. When I said as much in my SF/F survey class, one student protested, saying he didn’t think there was anything particularly bad about Lovecraft’s prose. “Well, try this,” I suggested. “When you go home, read some of his sentences out loud, and we’ll revisit this next class.” Sure enough, next class the student sheepishly admitted that , when reading Lovecraft’s sentences aloud, he could not get past how wordy and awkward and clunky so many of them are.

Lugubrious is the word I would use, and pretentious in the manner of someone who wants to demonstrate a large vocabulary without really knowing how. Take, for example, the opening sentence of At the Mountains of Madness: “I am forced into speech because men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why.” While not one of his more egregious constructions—I’ll get to one of those in a moment—it is typical of Lovecraft’s typically forced cadences. “I am forced into speech” is precisely the kind of phrasing that earns my students an “awk.” in the margins, indicating that, while not technically incorrect grammatically, is still quite awkward and should be rethought. “Regrettably, circumstances compel me to speak, “ or “I must, reluctantly, speak up,” would be improvements, but not great ones; better to start with the reason why the narrator is “forced,” with something like, “The refusal of my fellow scientists to listen to me has left my no choice but to speak up.” Again, not elegant, but clearer: “men of science have refused to follow my advice without knowing why” is a little confusing, as the “why” is too vague—and also, how often are we likely to follow someone’s advice when we don’t know why we should?

Perhaps this seems nitpicky, and it is, but such phrasing and sentence structure is pervasive throughout Lovecraft’s corpus. The opening sentence of Mountains is more or less inoffensive, but then the second paragraph gives us this behemoth:

In the end I rely on the judgment and standing of the few scientific leaders who have, on the one hand, insufficient independence of thought to weigh my data on its own hideously convincing merits or in the light of certain primordial and highly baffling myth-cycles, and on the other hand, sufficient influence to deter the exploring world in general from my rash and overambitious programme in the region of those mountains of madness.

Woof. I won’t parse all that—that would take too long, and I have other old gods to fry—but perhaps you get a sense of Lovecraft’s prose, and why readers with a low threshold for bad writing wouldn’t get more than a few sentences into his fiction before tossing it aside and writing Lovecraft off as merely a “pulp” writer.

Well, to be fair, he was a pulp writer, one of the many whose often lurid stories were published in cheap paperbacks and magazines; but out of that milieu came a handful of authors who gave us some persistent and enduring—albeit deeply problematic—characters and stories. Robert E. Howard created Conan the Barbarian, and with him a strain of proto-fantasy that resisted gentrification by Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Edgar Rice Burroughs—whom Atticus Freeman (Jonathan Majors) is reading at the start of Lovecraft Country—wrote all the John Carter of Mars novels, as well as numerous other SF works, but also created Tarzan. And though he was not in quite the same milieu, Englishman H. Rider Haggard invented the archaeological adventure story with novels like King Solomon’s Mines and She, without which we would not have Indiana Jones or Tomb Raider.

And then there’s Lovecraft, who despite his poor writing and shaky storytelling, profoundly influenced a generation of horror novelists and filmmakers. Unlike Howard and Burroughs, he did not have any memorable characters (unless you count the old god Cthulhu, but more on that below). What is so compelling about Lovecraft? His “mythos”—which imagined a malevolent universe populated by old gods and monsters that exist beyond the capacity of science and reason to comprehend them; much of his fiction is preoccupied with what happens when we mere mortals accidentally stumble into their ken. Spoiler alert: it never goes well for we mortals, who, if we’re lucky, are merely killed; the unlucky go mad, and the unluckiest somehow keep our minds but live with the crushing existential dread of knowing a cosmic truth that haunts us. Or as Lovecraft puts it at the start of “The Call of Cthulhu”:

The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents. We live on a placid island of ignorance in the midst of black seas of infinity, and it was not meant that we should voyage far. The sciences, each straining in its own direction, have hitherto harmed us little; but some day the piecing together of dissociated knowledge will open up such terrifying vistas of reality, and of our frightful position therein, that we shall either go mad from the revelation or flee from the deadly light into the peace and safety of a new dark age.

The “Cthulhu” in question is the old god that became central to Lovecraft’s mythos, to the point that it is now called the “Cthulhu Mythos.” It is a hideous, enormous tentacular horror that stalked the earth in its pre-pre-prehistorical days, but now lies slumbering beneath the earth. Its dreams infect the sensitive and give them visions of madness, or on occasion drive them actually mad. And, as chronicled in the story “The Call of Cthulhu,” sometimes tectonic events will drive his lair above the sea’s surface—at which point, eldritch hijinks ensue.

(If you want a rather hilarious rundown of Cthulhu &co.’s origin story, read Neil Gaiman’s “I, Cthulhu,” in which the old god in question recounts his tale in a fireside chat).

Lovecraft, a native New Englander, was deeply influenced by his home’s geography and its history. The vast majority of his fiction is based in, or connected to, a constellation of fictional small towns in Massachusetts—the principal one being Arkham, which houses Miskatonic University, with which many of his protagonists are affiliated. Beyond providing its geography, Lovecraft’s mythos is rooted in the region’s theocratic history: as has been discussed by a significant number of scholars, Lovecraft’s fiction is deeply influenced by the fire-and-brimstone Calvinism of New England’s Puritan settlers, in which humans are characterized as pitiful insects before God, whose only worth is to grovel before his greatness in the vain hope that he might grant salvation. The Cthulhu Mythos articulates this sort of Puritan self-abnegation, but without the hope of salvation—Lovecraft was a militant atheist, and took from the Puritan legacy mortals’ meaninglessness, without the hope.

Those unfamiliar with Lovecraft but steeped in the DC comics universe (though honestly I can’t imagine there are many of you in that particular Venn diagram) probably heard a bell go off at the name “Arkham.” Because, yes—the notorious Arkham Asylum of Batman and other Gotham-related tales is an overt reference to Lovecraft. The giant squid Ozymandias uses to destroy New York at the end of Watchmen is a nod to Cthulhu. The shape-shifting alien of The Thing is totally Lovecraftian. The xenomorph of the Alien franchise owes its existence to Lovecraft’s legacy. Buffy the Vampire Slayer is more indebted to Lovecraft than to Bram Stoker–its spinoff Angel perhaps even more so. As does, as I have written at some length, The Cabin in the Woods. And, well, I wouldn’t necessarily say Stephen King wouldn’t have a career without Lovecraft—but it would have been a very different career. To take just one example, It is probably the most Lovecraftian story there has been outside Lovecraft himself.

I could go on, but you probably get the point. Nobody will ever laud Lovecraft for his art, which is fair, but like a handful of his pulp compatriots, he has created compelling tropes that have lodged themselves in our collective imagination. But also like those of Burroughs and Howard and Haggard, they are deeply problematic. Conan the Barbarian is a veritable distillation of masculine characteristics that in the present moment we call toxic; H. Rider Haggard both traded on and furthered colonialist, racist representations of Africa and Africans as barbaric and hypersexualized; Burroughs did the same with Tarzan. In an early scene of “Sundown,” the first episode of Lovecraft Country, Atticus walks down a country road with an older Black woman after their bus had suffered a breakdown, and they were refused a ride in the pickup truck that came for them. When she asks him about the book he’s been reading, Burroughs’ A Princess of Mars, Atticus describes the travails of its hero John Carter. “Wait,” she interrupts him. “He’s a Confederate officer?” “Ex-confederate,” Atticus corrects her, but she’s having none of it. “He fought for slavery,” she says. “You don’t get to put an ‘ex’ in front of that.”

It’s a brief exchange, but a sharp one, and part of the point of Lovecraft Country is to interrogate Lovecraft’s legacy and influence—for, as I mentioned at the start of this post, Lovecraft was a virulent racist, and that racism informed his writing. China Miéville puts it quite well in his introduction to the Modern Library edition of At the Mountains of Madness:

Lovecraft was notoriously not only an elitist and a reactionary, but a bilious and lifelong racist. His idiot and disgraceful pronouncements on racial themes range from pompous pseudoscience—“The Negro is fundamentally the biologically inferior of all White and even Mongolian races”—to monstrous endorsements—“[Hitler’s] vision is … romantic and immature … yet that cannot blind us to the honest rightness of the man’s basic urge … I know he’s a clown, but by God, I like the boy!” This was written before the Holocaust, but Hitler’s attitudes were no secret, and the terrible threat he represented was stressed by many. (Lovecraft’s letter was written some months after Hitler had become chancellor). So while Lovecraft is here not overtly supporting genocide, he is hardly off the hook.

As Miéville notes, one of the common defenses offered of Lovecraft’s racism and anti-Semitism is that, well, that was what things were like at that time. As one of my students said, “It was the 1920s and 30s. Everyone was racist then.” To which I responded, well, no. There were actively antiracist white people then, and there were racists, but then there were also RACISTS—the lower-case group being people who did not question the overt societal ethos of white supremacy, and thought that Hitler fellow perfectly dreadful, but did not otherwise give it much thought; and then the latter, which were the Lovecrafts of the world—people actively and vocally championing white supremacy and superiority, opining at length on the inferiority of darker-skinned peoples, who saw in Hitler a brave and honest truth-teller, and who—like Lovecraft—endorsed eugenics and phrenology. So, no … Lovecraft was not merely “of his time” where his racial animus was concerned; he was in the vanguard.

(That being said, I get a bit squirrelly in making this distinction, because part of the cognitive dissonance of our present moment has proceeded from the tacit assumption that only all-caps racism is truly pernicious, or for that matter is the only real racism—that if you’re not hurling the N-word at Black people, or burning crosses, or otherwise behaving like every southern sheriff in every Hollywood movie about racism, then the charge is unfair. And when we’ve come to associate the terms “racism” and “racist” with those extreme behaviours, it makes it difficult for white people to make an honest reckoning with systemic racism and our complicity in it).

Lovecraft is thus an interesting figure to consider in our present moment of racial and historical reckoning, when such literal edifices as statues and monuments memorializing figures and events associated with slavery and institutional racism are being brought down. It’s easy enough to endorse the removal of Confederate monuments; it gets more complicated when the legacies and histories of the people memorialized are themselves more complicated. Does the authoring of the Declaration of Independence give slave-owning Thomas Jefferson a pass? Does Winston Churchill’s leadership during WWII outweigh his lethal policies in India?

Lovecraft had his own moment of statuary removal several years ago. Since 1975, the World Fantasy Award—along with such SF/F awards as the Hugo and Nebula— has been one of the most prestigious honours in the world of genre fiction. The very first awards were bestowed at the World Fantasy Convention, held in 1975 in HP Lovecraft’s home city of Providence, Rhode Island. In Lovecraft’s honour, the statuette was a stylized, elongated bust of his face—and so it remained for the next four decades.

As SF/F has become less and less the near-exclusive territory of white male authors, and grown to include more diverse writership and readership, the predictable backlashes have occurred—not least of which being the campaign by the so-called “Sad Puppies,” who were up in arms that the Hugo Awards were too woke and were eschewing “real” SF/F in favour of novels and stories written by social justice warriors. (If you want to read my rant about it at the time, click here). This was also the time of Gamergate, and—well, I don’t want to rehash that bit of asshattery, so of you’re unfamiliar, Google it. In this same time frame, there was a lot of pressure to retire the Lovecraft statuette. Authors of colour who had been awarded the “Howard,” as it is called (H.P. stands for Howard Philips) pointed out what a tainted honour it was to be lauded for their work with the visage of a man who considered them less than human.

And so the Howard was retired, and a new trophy was created, with all of the predictable hue and cry from those who, anticipating the protests about Confederate statues, called the retirement of the Howard an erasure of history—and an erasure of Lovecraft’s work.

Myself, I prefer the new trophy, and I reject the suggestion that the change is an erasure of any kind. It strikes me that what gets lost in the polarized debate about monuments and legacies and who we should memorialize is the overwhelming value of the debate itself. At the end of the day, whether or not the statue comes down, or whether or not a literary trophy gets a makeover, is at least a little bit beside the point: what I find encouraging in these moments is that arguments that have largely been had on the fringes have become more central. Do I think statues of Thomas Jefferson and Winston Churchill should be torn down? Actually, no—I do not. But I do think their histories and legacies need closer interrogation, and the tacit hagiography that attaches to them needs dispelling.

The same goes for those authors whose works resonate still today. Those influences are still powerful. But how we choose to be influenced, or how we critically approach the nature of that influence, is something else entirely. I’m seeing a lot of that in my current research with how fantasy as a genre is transforming what was, in its origins, a deeply conservative, reactionary, and religious sensibility, into a far more secular, humanist, and progressive one.

Not least of which are novels like Lovecraft Country, and its current adaptation on HBO.

The past two weeks have been an unforgivable lapse on my part, particularly so because I neglected to post on the text that was the original inspiration for this course: Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. That I didn’t manage to get anything up on this beautiful novel—which I count as one of the best of the past twenty years—is rather embarrassing. It wasn’t for lack of anything to say: I have copious notes on magical realism, the way in which the novel uses genre(s) to allegorize intersectional identities, and finally I had planned a post about allusion, in which I would have talked about Oscar Wao and Stranger Things.

The past two weeks have been an unforgivable lapse on my part, particularly so because I neglected to post on the text that was the original inspiration for this course: Junot Díaz’s The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao. That I didn’t manage to get anything up on this beautiful novel—which I count as one of the best of the past twenty years—is rather embarrassing. It wasn’t for lack of anything to say: I have copious notes on magical realism, the way in which the novel uses genre(s) to allegorize intersectional identities, and finally I had planned a post about allusion, in which I would have talked about Oscar Wao and Stranger Things.

Why Fun Home?

Why Fun Home?

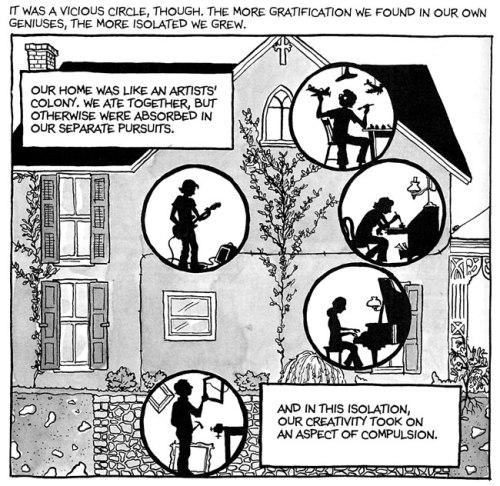

The opening chapter is titled “Old Father, Old Artificer,” an allusion to the final line of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.” Out of the gate, Bechdel at once identifies her graphic memoir with an august canon, and ironically signals this identification as transgression. It is a beautifully audacious beginning that reflects back upon the traditional strictures of literary canon, highlighting the fact that not only is this memoir a comic book, it is also written by a queer woman.

The opening chapter is titled “Old Father, Old Artificer,” an allusion to the final line of James Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man: “Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead.” Out of the gate, Bechdel at once identifies her graphic memoir with an august canon, and ironically signals this identification as transgression. It is a beautifully audacious beginning that reflects back upon the traditional strictures of literary canon, highlighting the fact that not only is this memoir a comic book, it is also written by a queer woman.

Why Station Eleven?

Why Station Eleven? As I quoted Charlie Jane Anders saying in her review of Zone One, Colson Whitehead goes out of his way to subvert generic expectations: not the structural, large-scale expectations of a given generic form, but the small-scale satisfactions and symbolic resolutions that that form tends to offer. Which is to say: Zone One provides the expected and by now rote depictions of post-apocalyptic survivalism, including interludes of relative safety in secure locations, followed by the inevitable collapse of that security as the dead overwhelm the barricades. We meet a veritable checklist of ordinary folk turned accomplished zombie killers, religious fanatics, madmen, would-be warlords, opportunists and thieves, families desperate to stay together in the face of disaster.

As I quoted Charlie Jane Anders saying in her review of Zone One, Colson Whitehead goes out of his way to subvert generic expectations: not the structural, large-scale expectations of a given generic form, but the small-scale satisfactions and symbolic resolutions that that form tends to offer. Which is to say: Zone One provides the expected and by now rote depictions of post-apocalyptic survivalism, including interludes of relative safety in secure locations, followed by the inevitable collapse of that security as the dead overwhelm the barricades. We meet a veritable checklist of ordinary folk turned accomplished zombie killers, religious fanatics, madmen, would-be warlords, opportunists and thieves, families desperate to stay together in the face of disaster. While some of the gods Shadow meets are sedentary, like Mr. Ibis and Mr. Jaquel in their Cairo, Illinois funeral home, or Czernobog and the Three Sisters in Chicago, the novel itself is decidedly peripatetic and conveys a powerful sense of rootlessness. To be certain, this perambulatory quality is predominantly communicated by Shadow’s constant movement, crisscrossing the continent in Mr. Wednesday’s tow. But between his constant road-tripping and the depiction of the various old gods as marginal and forgotten, eking out an existence on what they can beg, scrape, swindle, or steal, the novel reimagines a common pre-WWII trope in American literature and popular culture: the romanticized figure of the drifter, the vagabond, the hobo.

While some of the gods Shadow meets are sedentary, like Mr. Ibis and Mr. Jaquel in their Cairo, Illinois funeral home, or Czernobog and the Three Sisters in Chicago, the novel itself is decidedly peripatetic and conveys a powerful sense of rootlessness. To be certain, this perambulatory quality is predominantly communicated by Shadow’s constant movement, crisscrossing the continent in Mr. Wednesday’s tow. But between his constant road-tripping and the depiction of the various old gods as marginal and forgotten, eking out an existence on what they can beg, scrape, swindle, or steal, the novel reimagines a common pre-WWII trope in American literature and popular culture: the romanticized figure of the drifter, the vagabond, the hobo.

Wednesday’s almost offhand dismissal of Christianity’s ubiquity speaks to a question I raised in class: if gods exist by way of people’s worship, then where—in a nation in which

Wednesday’s almost offhand dismissal of Christianity’s ubiquity speaks to a question I raised in class: if gods exist by way of people’s worship, then where—in a nation in which