This is the first of two posts dealing with war as a critical trope in The Lord of the Rings. I’ve been thinking for a long time now about the role of violence and cruelty in fantasy generally, and Tolkien specifically; at some stage in the near future I’ll be posting something about the Uruk-hai, torture, and rapine. What’s on my mind this week, however, is war more generally: war as an organizing principle in The Lord of the Rings, what role it plays thematically and otherwise, and the ways in which battle functions as a redemptive and ennobling experience. In class this past week we finished the first book of The Return of the King, with its climactic battle in which the forces of Sauron meet with temporary defeat. What I want to suggest in this post is that however much Tolkien was steeped in the myth, legend, and history of the Middle Ages—and indeed created in The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings a compelling modern retread of medieval preoccupations—by the end of his masterpiece and in such supplemental texts as his appendices and Unfinished Tales, the scope and scale of Middle-earth has become identifiably twentieth-century.

Considering that The Lord of the Rings was written during and immediately after the Second World War, there is a not insignificant amount of criticism and interpretation that looks for parallels between Tolkien’s narrative and the events raging in the world at the time of writing. Tolkien himself tended to deny real-world correlations: Sauron was not Hitler, Mordor was not Nazi Germany. In so saying, he echoed and anticipated legions of fantasists who reject straightforwardly allegorical readings of their texts. And with good reason: such reductive this=that interpretations deny narratives like Tolkien’s their nuance and complexity (and by contrast, otherwise compelling stories can become hackneyed when they too-obviously employ obvious correspondences; indeed, the most cringeworthy parts of the Narnia Chronicles come when C.S. Lewis slaps on the Christian allegory with a trowel).

That being said, The Lord of the Rings’ resonances with its recent and contemporaneous history can be hard to ignore. As I observed to my students this week, it would be hard to credit that a thoughtful and deeply intelligent man like Tolkien would not find himself influenced by traumatic, world-shaping traumas like the two world wars. Tolkien himself fought in the First World War and was wounded at the Battle of the Somme, badly enough that he spent several years convalescing (during which time he shaped the substance of the mythology that would become The Silmarillion). It is easy to imagine how the pastorally-minded Tolkien was traumatized not just by the horror and violence of the trenches, but by the way the verdant fields of France and Belgium were transformed into blasted horrorscapes of mud, blood, broken metal, and corpses. Frodo and Sam’s traversal of the Dead Marshes and Dagorlad (the “Battle Plain”) is about as vivid a recreation of the Western Front as possible while still taking place in Middle-earth. In the Dead Marshes, the see the faces of the dead under the water. Frodo says:

I have seen them … They lie in all the pools, pale faces, deep deep under the dark water. I saw them: grim faces and evil, and noble faces and sad. Many faces proud and fair, and weeds in their silver hair. But all foul, all rotting, all dead.

Gollum concurs, adding that “There was a great battle long ago … They fought on the plain for days and months at the Black Gates.” The battle to which he refers is the battle fought by the Last Alliance of Elves and Men against Sauron, which ended with Isildur cutting the Ring from Sauron’s hand. The faces Sam and Frodo see beneath the marshes are the dead from that battle, and though it is uncertain whether they are specters or actually there (somehow sorcerously preserved), the image of dead faces peering up through foul water unavoidably evokes the experience of many in WWI who saw the dead submerged in water-filled craters and corpses disinterred from the mud by shellfire. After they pass on from the Dead Marshes, Frodo and Sam follow Gollum through Dagorlad, which even a thousand years after the war between the Last Alliance and Sauron is still a reeking, desolate landscape. At one point they take shelter in a close facsimile of a shell-crater:

Frodo and Sam crawled after [Gollum] until they came to a wide almost circular pit, high-banked upon on the west. It was cold and dead, and a foul sump of oily many-coloured ooze lay at its bottom. In this evil hole they cowered, hoping in its shadow to escape the attention of the Eye.

(It is worth noting here that while soldiers on either side of the Western Front did not have to worry about the malevolence of a Dark Lord, there was a constant struggle to not be visible. The superstition about not lighting three cigarettes on the same match was born out of the fear of snipers; and any soldier managing to survive his first front-line posting learned the lesson of staying low.)

Observing the WWI resonances in these chapters is by no means original or new: it is, indeed, a staple of Tolkien biography and criticism to note this rare moment where his own experience bleeds into the text (pun intended). The imagery is obvious enough that Tolkien himself acknowledged it, saying in a letter that “The Dead Marshes and the approaches to the Morannon owe something to Northern France after the Battle of the Somme.” (Not content to leave it there, however, he adds, “They owe something more to William Morris and his Huns and Romans, as in The House of the Wolfings or The Roots of the Mountains.”)

By contrast, there is little or nothing overtly referencing the global conflict that raged while he wrote The Lord of the Rings—too old for service at that point, he had no firsthand experience of the war, and Oxford was never a target for the Luftwaffe’s bombs. That being said, it is difficult not to see the shift in focus and scope over the course of The Lord of the Rings as reflecting the global changes wrought by a global war. If Tolkien’s storytelling impulses had started with traditional quest-romance in The Hobbit and into The Fellowship of the Ring, by the end of The Return of the King the novel’s scope has expanded to encompass most of Middle-earth. The Hobbit and Fellowship both exhibit the limited scope of a quest narrative, with a narrative specific to the band of adventurers and, in both cases, more or less limited to the perspective of a single character. Both proceed from romance’s basic narrative premise, namely the essaying forth from enclaves of safety and security into an unknown (unknown to the hobbits, at any rate) wilderness full of dangers.

Starting with The Two Towers however, the narrative fractures, and the preoccupations of the principal characters have less to do with the quest per se than with what can really only be characterized as geopolitical concerns. I never would have thought to hear myself using the word “geopolitical” with regard to The Lord of the Rings, but it is apt when one considers the larger picture of the imminent war with Sauron. It is telling that just before Frodo determines to desert the Fellowship and set off on his own to Mordor—breaking not just the Fellowship, but the single narrative thread the novel has so far followed—he has a totalizing vision of Middle-earth from the Seat of Seeing atop the hill of Amon Hen:

But everywhere he looked he saw signs of war. The Misty Mountains were crawling like anthills: orcs were issuing out of a thousand holes. Under the boughs of Mirkwood there was deadly strife of Elves and Men and fell beasts. The land of the Beornings was aflame; a cloud was over Moria; smoke rose on the borders of Lorien.

Horsemen were galloping across the grass of Rohan; wolves poured from Isengard. From the havens of Harad ships of war put out to sea; and out of the east men were moving endlessly: swordsmen, spearmen, bowmen upon horses, chariots of chieftans and laden wains. All the power of the Dark Lord was in motion.

In his book Inventing the Middle Ages, Norman Cantor lauds Tolkien for depicting a medieval setting in relatively realistic terms, “not the Arthurian heroism of golden knights but the wearying, almost endless struggle of the little people against the reality of perpetual war and violent darkness.” Middle-earth, he asserts, presents “the medieval world at its most bellicose, destructive, and terrible moments: the Age of the Barbarian Invasions in the fifth and sixth centuries; the Hundred Years’ War in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries.” Perpetual war is the crucial designation here, as indeed any casual familiarity with the European Middle Ages is one of near-constant skirmishes, campaigns, shifting alliances and loyalties, punctuated with larger battles and wars, but always with some armed strife smoldering in some corner of the continent. Our image of Middle-earth—once we leave the Shire behind—is precisely of that sort of constant conflict, whether expressed by the relics of old wars like the Barrow-Downs, or the ongoing skirmishes between Gondor and Mordor as described by Boromir. And even where there is no battle in progress, there is always one waiting for those who trespass into enemy territory, such as occurs in Moria.

If the medieval condition is one of perpetual war, however, Tolkien builds to conflict on a much larger and indeed totalizing scale. Frodo’s vision from Amon Hen is a foretaste of what is to come and it is markedly continent-wide, stretching from the Misty Mountains to Mirkwood to Lorien, and finally south to Gondor. The narrative itself expands outward to encompass broader and more varied geographies, and broader and more varied concerns. Even Sam and Frodo, whom can be said to be carrying on the quest-narrative, have in their encounter with Faramir and his rangers an impromptu education in history and geopolitical considerations, as well as bearing witness to such considerations manifested in the rangers’ battle with the Men of Harad. Elsewhere, Aragorn, Legolas, and Gimli become embroiled in Rohan’s struggle with Saruman; Merry and Pippin find themselves allied with Treebeard and the Ents, and witness the defeat of Isengard while their friends are still fighting at Helm’s Deep; Pippin finds himself caught up in Gondor’s intrigues, stuck between the dueling wills of Denethor and Gandalf (between a rock and a hard case, one might say); he swears his service to Gondor; Merry similarly pledges his sword to Rohan, and is witness to the Battle of Pelennor fields.

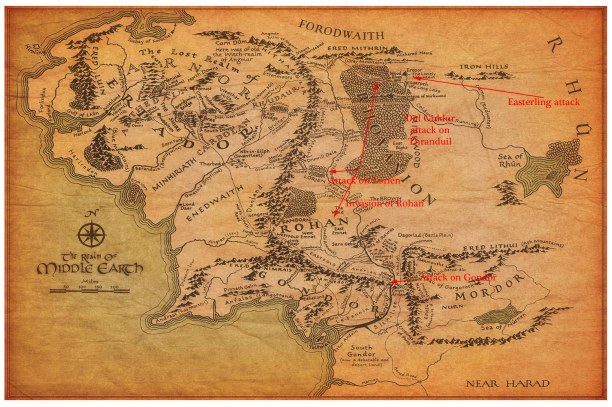

All this is by way of highlighting the ever-widening scope of The Lord of the Rings, but even these examples are only hints of a vaster conflict, one that only really becomes apparent in such supplementary texts as the novel’s appendices or Unfinished Tales. There we learn that Sauron’s forces attacked more or less simultaneously along an east-west front running almost the entire length of Middle-earth: as Gondor was besieged, so too was eastern Rohan invaded, Lothlorien and the elves of Mirkwood attacked, and a force of Easterlings descended on Dale and the Lonely Mountain. A sample from the appendices:

All this is by way of highlighting the ever-widening scope of The Lord of the Rings, but even these examples are only hints of a vaster conflict, one that only really becomes apparent in such supplementary texts as the novel’s appendices or Unfinished Tales. There we learn that Sauron’s forces attacked more or less simultaneously along an east-west front running almost the entire length of Middle-earth: as Gondor was besieged, so too was eastern Rohan invaded, Lothlorien and the elves of Mirkwood attacked, and a force of Easterlings descended on Dale and the Lonely Mountain. A sample from the appendices:

At the same time as the great armies besieged Minas Tirith a host of the allies of Sauron that had long threatened the borders of King Brand crossed the River Carnen, and Brand was driven back to Dale. There he had the aid of the Dwarves of Erebor; and there was a great battle at the Mountain’s feet. It lasted three days, but in the end both King Brand and King Dain Ironfoot were slain, and the Easterlings had the victory. But they could not take the Gate, and many, both Dwarves and Men, took refuge in Erebor, and there withstood a siege.

After the destruction of the Ring, the appendix goes on to say, the Dwarves of Erebor and Men of Dale emerged and routed their enemy. So too did Celeborn and Galadriel take their forces from Lothlorien to destroy Dol Guldur, and there under the trees of Mirkwood meet up with the forces of Thranduil (Legolas’ father and king of the wood-elves). According to Tolkien’s chronology, the events of this great, final battle take place over the course of about two weeks—two weeks in which all of Middle-earth is locked in simultaneous battle.

Any sense that the War of the Ring is anything less than a global conflict is further dispelled by Gandalf’s story in Unfinished Tales about how he conceived of his scheme to send Bilbo along with Thorin and the Dwarves to Erebor. Knowing that the Necromancer in Dol Guldur was in fact Sauron, Gandalf fears what dire use he might make of the dragon Smaug:

You may think that Rivendell was out of his reach, but I did not think so. The state of things in the North was very bad. The Kingdom under the Mountain and the strong Men of Dale were no more. To resist any force that Sauron might send to regain the northern passes in the mountains and the old lands of Angmar there were only the Dwarves of the Iron Hills, and behind them lay a desolation and a Dragon. The Dragon Sauron might use with terrible effect.

When Thorin accuses Gandalf of having ulterior motives for helping him, Gandalf replies “You are quite right … If I had no other purposes, I would not be helping you at all. Great as your affairs seem to you, they are only a small strand in the great web. I am concerned with many strands.” Gandalf has always appeared as a wise counselor; here we see him as a shrewd strategist operating on a global scale. One of the fascinating parts of returning to The Lord of the Rings this term as I have has been seeing how Tolkien retroactively folded the events of The Hobbit into the broader sweep of Middle-earth’s history: not just an unexpected journey, but a shrewd move on the geopolitical board with deeply significant benefits many, many years later. As Gandalf concludes his tale:

It might all have gone very different indeed. The main attack was diverted southwards, it is true; and yet even so with his far-stretched right hand Sauron could have done terrible harm in the North, while we defended Gondor, if King Brand and King Dain had not stood in his path. When you think of the great Battle of Pelennor, do not forget the Battle of Dale. Think what might have been. Dragon-fire and savage swords in Eriador! There might be no Queen in Gondor. We might only hope to return from the victory here to ruin and ash. But that has been averted—because I met Thorin Oakenshield one evening on the edge of spring not far from Bree. A chance-meeting, as we say in Middle-earth.

The broader point I am making here is that, while Tolkien does not effect one-to-one analogies with his contemporaneous history, the global scope with which The Lord of the Rings ends does reflect—however obliquely—the radical changes wrought by the Second World War. Britain had of course been a global power for some two centuries, but the twentieth century ushered in a terrible era of total war that had not been possible in previous centuries. The Hobbit and The Fellowship of the Ring depict a neo-medieval world in terms of the traditional scope of the quest-romance; by the end of The Return of the King, the geopolitical conflict consuming an entire continent is the unmistakable product of the fraught twentieth century.

That painting depicting the siege of Minas Tirith seems way out of scale to what Tolkien described. Rohan brought 6000, which would have been useless against that horde. One thing Tolkien got right was the size of the armies.

Norman Cantor lauds Tolkien for depicting a medieval setting in relatively realistic terms, “not the Arthurian heroism of golden knights but the wearying, almost endless struggle of the little people against the reality of perpetual war and violent darkness.”

I thought he did kind of depict the heroism of golden knights. We see feudal societies at the top level – but not much is said of all the servants who bring them meals, etc., in Rivendell and elsewhere. (Imagine being an immortal who has to empty Elrond’s chamber pot for thousands of years.) All the kings on the Good side are noble. I wouldn’t probably have wanted a warts-and-all, Song of Ice and Fire approach but it’s a bit like The Godfather level of an organization rather than Donnie Brasco. Tony Robinson (aka Baldrick) did a show called The Worst Jobs in History. Even in Middle Earth there were a lot of elves, dwarves, and humans doing a lot of really dirty jobs. Or, it’s like Upstairs, Downstairs (or Downton Abbey) if they only showed us the Upstairs. Or…Harry Potter if we never see or hear anything of the House Elves.

Now, I get it. Tolkien’s work was based on poems like Beowulf. He wasn’t interested in what has lately become fashionable in fantasy, to describe in fetishistic detail how the horses were saddled, how the armor was made, etc., and to show how horrible a life it was to be any kind of peasant. But that’s the point – he does, sort of, do an Arthurian type of fantasy, a Beowulf fantasy. He leaves all that other stuff implied. (Even Frodo was kind of upper class, in a hobbit way.)