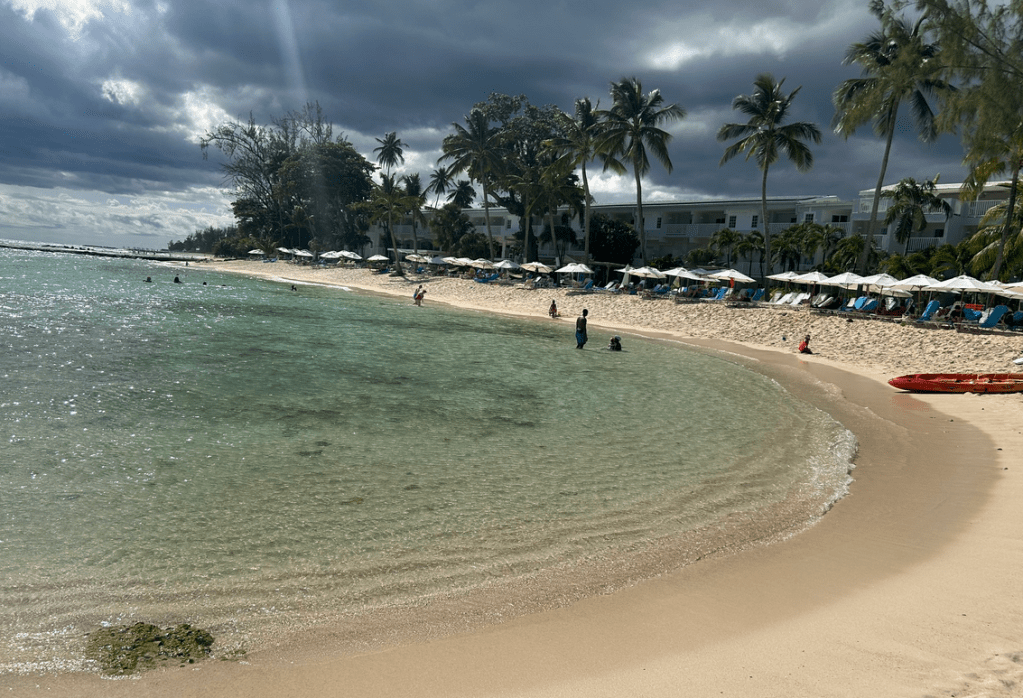

My wife Stephanie and I recently returned from ten much-needed days in Barbados. The last time we went on vacation was four years ago—also to Barbados, in the auspicious month of March 2020. So, yeah … we ended up having to come home early when the Prime Minister got on TV and told Canadians abroad to come home. Which sort of put a pall on the otherwise wonderful holiday.

So we were more than ready for our return. It had been an unusually busy school year, and I was looking forward to one of my favourite activities while vacationing: reading. In the weeks leading up to our departure, I started three piles of books. Pile one was novels I’ve purchased but not yet read; pile three was unread nonfiction; the middle pile was the ever-shifting lineup of books I would bring with me, which changed day by day as I moved titles back and forth between the piles. Based on the fact that we had ten days, I kept the reading pile to what I thought was a reasonable volume, often swapping out two or three shorter texts for one chunky one, or vice versa.

I should add that what I considered a “reasonable volume” of reading evoked profound scepticism from Steph, who felt I was being excessively optimistic in how much I would be able to read in ten days—which to her mind was an issue because of the space the books would take up in our luggage.

(And don’t get at me about the virtues of e-readers. I will stipulate to all those virtues, while still hewing to my luddite ways with paper books. Reading should be pleasurable, reading on vacation doubly so, and I will always love the feel and look of a physical book infinitely more than a slim slab of silicone, no matter how convenient the latter.)

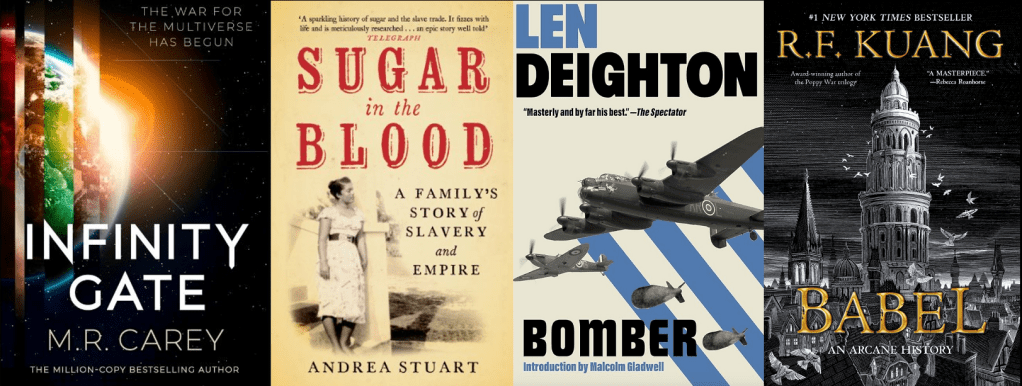

I ultimate settled on four chunky reads: Infinity Gate by M.R. Carey; Sugar in the Blood by Andrea Stuart; Bomber by Len Deighton; and Babel by R.F. Kuang.

And yes: I read them all.

M.R. Carey, Infinity Gate. Carey has rapidly become one of my favourite contemporary SFF authors. He is most famous for The Girl With All the Gifts, a brilliant zombie apocalypse novel that was adapted into a quite good film starring Glenn Close, Gemma Arterton, and Paddy Consadine. He followed that up with The Boy on the Bridge, set in the same world with an intersecting storyline. He then wrote the rather astonishing Rampart Trilogy: The Book of Koli, The Trials of Koli, and The Fall of Koli. Like his zombie novels, the trilogy is also post-apocalyptic, set in Britain in a distant future in which a catastrophe has almost wiped out humanity and reduced them to premodern circumstances and all of nature has mutated to be hostile to the survivors.

Infinity Gate had been sitting on my shelf since last September. On seeing it I purchased it right away and started reading. But about twenty pages in I forced myself to stop. The school year was shaping up to be the busiest I’ve had in my academic career, and I couldn’t let myself indulge in a long novel (500 pages) that would suck me in. So it sat, unread, until the day before our departure.

I was not disappointed. Though it departs from Carey’s previous post-apocalyptic preoccupations, it nevertheless hits many of the same thematic sweet spots. It begins in a familiar place: a world on the brink of environmental and civilizational collapse. A Nigerian physicist, recruited to a lavishly funded Hail Mary project to discover a last-ditch solution for the world’s imminent demise, invents technology that allows her to move between different possible Earths—a mode of stepping between alternative realities in an infinite multiverse.

I’ve recently been kicking around a post or two musing about the recent prevalence of multiverse-based stories, from Everything Everywhere All At Once to the Spider-Verse movies, so I’ll have a lot more to say about Infinity Gate soon. But I do want to note that one of the great things about Carey’s world-building—aside from the simple fact that a chunky novel has more depth than your average Marvel property—is that he really engages with the implications of an infinite multiverse. Which is to say: every possible iteration of our planet exists, which includes countless timelines in which no version of humanity evolved, or in which the Earth is unliveable, or indeed where the planet simply never came together. On the other hand, there are millions of Earths with variations on primate-evolved humanity, and millions in which the intelligent species evolved from canines, felines, lizards, herbivorous mammals, and so on.

And as we quickly learn, thousands of these other Earths have developed interdimensional travel, and have formed a massive alliance called the Pandominion—into which the Nigerian physicist accidentally trespasses.

Andrea Stuart, Sugar in the Blood. Barbados has always had a special place in my heart, not least because my maternal grandmother’s family emigrated from there to Canada in the first decades of the twentieth century. We can trace our heritage back to the seventeenth century, a fact that, as I matured and learned more about the history of colonialism and the slave trade, inspired an increasing discomfort and ambivalence. We can, for example, locate our ancestors’ plantation on eighteenth century maps. And so, as much as I love Barbados, I’m also always aware of my family’s fraught history there.

Sugar in the Blood is a story of a similar such history, though from the perspective of a Black author whose enslaved ancestor was the bastard offspring of a wealthy planter. Andrea Stuart is a Barbadian-British historian; she traces her family back to her original white ancestor, an English blacksmith who took a chance on the promise of the colonial “adventure” and arrived on the island in 1630. Stuart then follows her ancestors’ struggles and successes, telling the broader history of Barbados, the Caribbean, and colonialism as she goes.

It is not an especially happy or uplifting history. When her white ancestors finally attain a measure of success and wealth after several generations of precarious farming, it comes from the blood and pain and death of countless enslaved Africans who were brought in great numbers to cultivate the cane fields that yielded “white gold,” the sugar that built obscenely large fortunes and filled the coffers of the British crown. When my mother first read this book and called to tell me about it, she accidentally called it Blood in the Sugar. Catching her error, Mom noted ruefully the serendipity of the misstatement, reflecting that it might almost be a more appropriate title. Stuart is frank and brutal in her recounting of Barbados’ centrality in the burgeoning sugar trade and its human cost, describing with unsparing detail the usually short lives of the enslaved as they worked in searing heat to harvest the knife-like sugar cane, as well as the dangers of operating the mills and presses that processed it.

As you might imagine, there is a not-insignificant cognitive dissonance that occurs when reading this history while on vacation in the place it occurred. That history lives in the present moment: in the food and drink, in the local dialect, in the vestiges of the British colonial presence. The sugar industry, though no longer the primary driver of the island’s economy—tourism now comprises the greater share—is still there: cane fields cover much of the island’s interior, rum remains a key export. And as a twenty-year resident of Newfoundland, it is always odd to find salt cod on many menus down there—itself a legacy of the triangular trade, as is the ubiquity of rum in Newfoundland.

As Stuart relates, Barbados is a post-imperial success story, having possessed one of the Caribbean’s most stable democracies since it won independence in 1966. And however fraught its history, Bajans are fiercely proud of their island.

Len Deighton, Bomber. I’d never read any of Deighton’s fiction prior to Bomber. The only book of his I’d read was Blood, Tears, and Folly, his acerbic history of WWII; as a systematic debunking of the gauzy mythos of “the good war,” it is second only to Paul Fussell’s Wartime for its unstinting refusal to sentimentalize any aspect of that conflagration. Bomber is very much of a piece, a polemic in the form of historical fiction that takes aim at the Allies’ strategic bombing campaign against Germany.

I picked up Bomber because I’ve been immersing myself in this particular history for almost two years now—research that started as the basis for an article on Randall Jarrell’s war poetry. In characteristic fashion it has mushroomed into an ever-expanding preoccupation that has several possible writing projects emerging. I’ve now read somewhere in the neighbourhood of seven or eight histories, with a few sitting on my shelf waiting to be read. (I also, for my sins, subjected myself to Masters of the Air, the recent mini-series about American B-17 crews. I’ll probably have more to say about it in a future post; suffice for the moment to say that, as the third in a series that started with Band of Brothers and continued with The Pacific, the quality of the storytelling has fallen rather precipitously.)

Bomber is the kind of historical fiction that manages to be compelling as fiction while also functioning solid history. It is a sprawling narrative that encompasses a huge cast of characters, including a group of British Lancaster crews, German night-fighters and their base personnel, the mission planners at RAF bomber command, the operators of a German radar station tracking the bombers, and the citizens of a German town that becomes the accidental target of the RAF raid and suffers a Dresden-like catastrophe. All of which takes place within a twenty-four hour period.

As a work of fiction, the novel is astonishing: Deighton handles the complexity of the narrative deftly and manages to imbue all the numerous characters with depth and nuance. Early on, it becomes clear what will happen at the story’s climax: the bombers will miss their intended target and instead bomb the town we encounter, a town with no military structures or strategic value. Knowing this does not denude the building tension as the bomber stream makes its way through the night. Just the opposite: Deighton communicates the textures of the town and its people, the good, bad, and ugly, to the point where what finally befalls them is nothing short of horrifying.

As a work of history, the novel is a trenchant indictment of Arthur “Bomber” Harris’ leadership of the RAF Bomber Command. As I’ve written about on this blog previously, Harris was a bloody-minded sociopath who dismissed the American strategy of daytime targeted bombing of military and industrial targets. Leaving aside the fact that the American claims to accuracy were wildly overblown, Harris pursued the “area bombing” of city centres on the premise that this would (1) kill or de-house thousands of German workers, and (2) break the German spirit so that they rose up and threw off Hitler’s regime (for this reason, the strategy also went by the name “morale bombing”). Spoiler: it did not work. At all. It did however result in a nearly 50% attrition rate for bomber crews, the destruction of countless cities and towns (many of which had no military value), and the deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians—some in such hellish cataclysms as the firebombing of Hamburg and Dresden. Deighton’s description of the effect of just such a firebombing at the culmination of the novel is genuinely harrowing.

R.F. Kuang, Babel. R.F. Kuang is a writer who’s been on my radar for some time, but I’ve only now managed to read any of her work. She is one of a new generation of SFF authors who bring a much greater, and much-needed, diversity to genre fiction. (Or, from the perspective of genre’s reactionary rump, she’s one of the legions of woke writers ruining SFF with her politically correct scolding. See here, and here, and here to get my thoughts on that particular attitude.) She has a trilogy of fantasy novels starting with The Poppy War that I am now eager to read, and more recently came out with Yellowface, a non-genre novel about an Asian-American writer who has her manuscript stolen by her white friend (also sitting on my shelf, waiting to be read).

But Babel is the one I’ve been keen to read since I first read about it. It takes place in the early 19th century in an alternative-history Great Britain in which silver possesses certain magical qualities and the British Empire—approaching the first apogee of its global power—is determined to use it to advance its imperial interests. It is not silver however that is inherently magical—rather, silver is the medium for magic that is effected through language. More specifically, when you take two words in different languages that can mean the same thing, inscribe them on either side a silver bar, and then speak them aloud, this produces a magical effect consonant with the words’ meaning. The crux however is that the greater the dissonance between the words, the more powerful the spell; or to put it another way, what remains untranslatable is the source of the power. And so in Kuang’s alternative 1830s, language is an exploitable commodity. As the British Empire expands and its influence spreads, this causes a linguistic convergence that reduces the power of spells employing English and European languages. Hence, the Babel Institute (a tower, naturally) at Oxford University labours to learn increasingly exotic tongues even as British military and commercial interests seek out new sources of silver.

To this end, the Babel Institute comprises an unusually racially and ethnically diverse student body, as it sponsors fledgling scholars from around the world whose fluency in their native languages is invaluable. Of course, the privileges and status afforded the “Babblers,” (1) does not inoculate them against the bigotry of the university’s rank and file, nor of the town of Oxford at large; (2) comes with a series of insidious strings attached; and (3) inspires in many of the students a profound ambivalence as they realize their linguistic talents are being employed in the service of imperial depredations of their home countries.

I won’t spoil the story by sharing any more—suffice to say I’ll be looking for an excuse to include this novel on future courses.