TL;DR: this year I’m being unequivocal about students’ use of AI. I’m banning it.

And yes, this is very much an exercise in spitting into the wind, fighting the tide, etc. Choose your metaphor. AI’s infiltration of every aspect of life seems inevitable at this point, but to my mind that makes an education in the humanities in which students engage with “The best which has been thought and said” (to use Matthew Arnold’s phrasing) all the more crucial, and all the more crucial that they do it without recourse to the banalizing effects of AI.

I’m profoundly sceptical of the claims made for AI’s potential, and not just because twenty-five years of Silicon Valley utopianism has given us the depredations of social media, monopolistic juggernauts like Amazon and Google, and a billionaire class that sees itself as a natural monarchy with democracy an also-ran annoyance. In the present moment, the best descriptor I’ve seen of AI is a “mediocrity machine,” something evidenced every time I go online and find my feeds glutted with bot-generated crap. “But it will get better!” is not to my mind an encouraging thought, not least because AI’s development to this point has often entailed the outright theft of massive amounts of intellectual property for the purposes of educating what is essentially a sophisticated predictive text algorithm.

But that is not why I’m banning use of AI in my classrooms.

To be clear: I say that knowing all too well how impossible it is to definitively ban AI. Unlike plagiarism proper, AI’s presence in student essays is at once glaringly obvious and infinitely slippery. With plagiarism, so long as you can find the source being copied, that evidence is ironclad. But AI is intrinsically protean, an algorithmic creation that potentially never produces the same result twice. And yet it’s always obvious, whenever I get an essay that is grammatically perfect but intellectually vacuous. A ChatGPT-authored essay is basically the uncanny valley in prose form: it looks like a reasoned and structured argument, but it lacks the idiosyncrasies and depth that make it, well, human. I’ll say this much for AI—it has pulled off the feat of making me grateful to find an essay riddled with grammatical errors and unreadable sentences. In the present moment, that’s the sign of a student actually doing the work.

But then, that’s the basic point: it’s doing the work that’s important. I recently read an interview with Texas teacher Chanea Bond on why she’s banning AI in her classroom. It’s a great interview, and she helped clarify some of my thinking on the subject. But what depresses me is that her stance is even remotely controversial—that she received a great deal of pushback on social media, much of it from fellow educators who see AI as a useful tool. To which Bond said: No, in Thunder. Which was not a response emerging from some sort of innate Luddism, but from her own experience of attempting to use AI as the useful tool so many claim it to be. “I envisioned that AI would provide them with the skeleton of a paper based on their own ideas,” she reports. “But they didn’t have the ideas—the analysis component was completely absent. And it makes sense: To analyze your ideas, they must be your ideas in the first place.”

This, she realized, was the root of the problem: “my students don’t have the skills necessary to be able to take something they get from AI and make it into something worth reading.” To develop a substantive essay from an AI-generated outline, one must have the writing skill set and critical acumen to grasp where the AI is deficient, and to see where one’s own knowledge and insights build out the argument. Bond’s students were “not using AI to enhance their work,” she observes, but are rather “using AI instead of using the skills they’re supposed to be practicing.”

And there’s the rub. In my lifetime, and certainly in my professional academic career, there has never been a time when the humanities has not been fighting a rearguard action against one form of instrumentalization or another. Tech and STEM are just the most recent (though they have certainly been the most overwhelming). The problem the humanities invariably faces is that it’s ultimately rooted in intangibles. Oh, there’s a whole host of practical abilities that emerge from taking classes in literature or philosophy or history—critical reading, critical writing, communication, language—and perhaps we could do a better job of advertising these benefits. But I’m also loath to play that game, for reducing humanities education down to a basic skillset not only elides its primary, intangible benefit, but also plays into the hands of administrators seeking to reduce the university to a job creation factory. In such a scenario, it’s all too easy to imagine the humanities reduced to a set of service courses—English transformed to basic composition, literature jettisoned; languages taught solely on the basis of what’s of practical use in industry; philosophy a set of business ethics classes; communication studies entirely instrumentalized, stripped of all inquiry and theory; and entire other departments simply shuttered, starting with classics and history and working down from there.

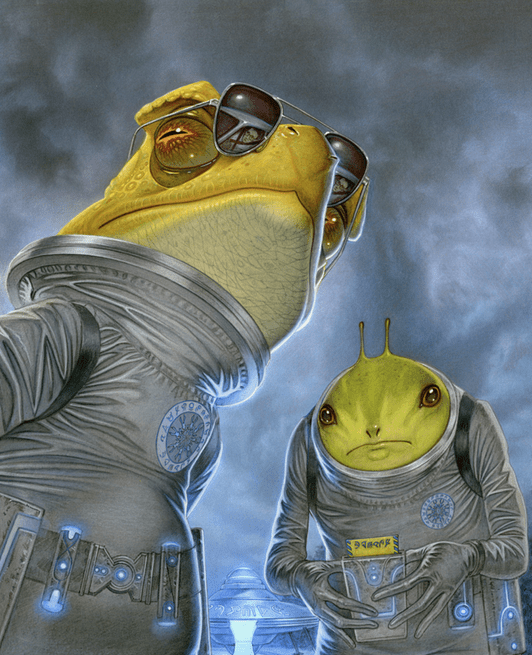

It may appear I have drifted from my original topic, but this sort of thinking is exactly the kind that believes AI can replace critical, intellectual, and creative work. What is both risible and infuriating about this assumption is that whatever sophistication AI has attained has come by way of scraping every available resource to be found online—every digitized book, every image, every video, a critical mass of which is other people’s intellectual property, all plundered to feed the AI maw. (And still, all it can produce are essays that top out in the C range in first year English classes.) I don’t think AI’s cheerleaders have grasped what a massive Ouroborosian exercise this is: as the snake consumes more and more of its tail there is less and less of it. The more we collectively rely on AI to do our thinking for us, the less creative, new, and genuinely revolutionary thought there will be to feed the beast. And as a result, the more stagnant and banal becomes the output.

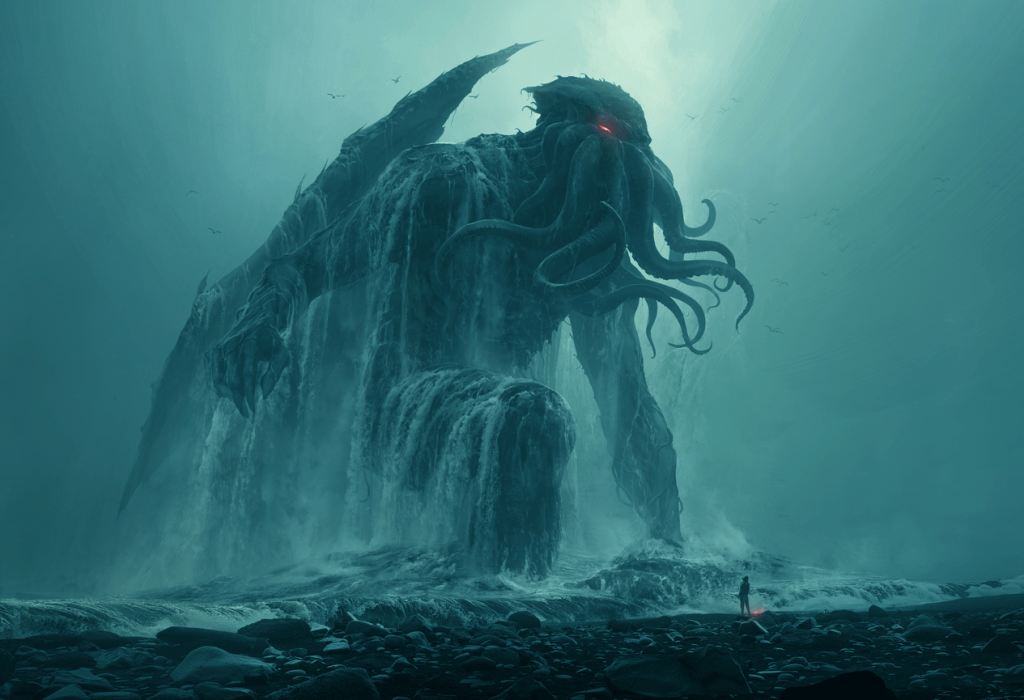

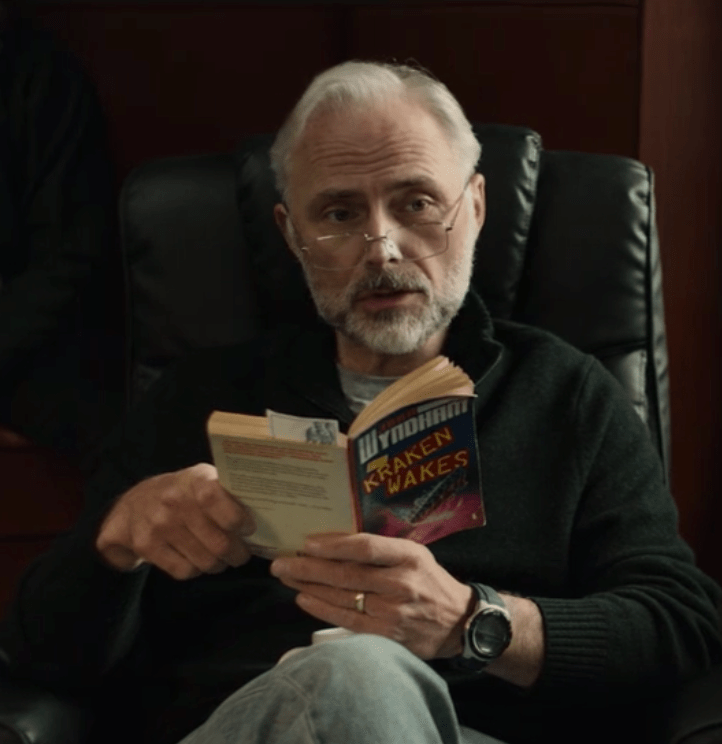

Last year I reread 1984 for a course I was teaching and was struck anew by the degree to which Orwell is less concerned with totalitarianism’s mechanisms of brutality than with the curtailment of people’s capacity to articulate resistance and dissent. His notorious Thought Police are just the crude endpoint of power’s expression; the more insidious project lies in removing the ability of people to think thoughts worth policing. Winston Smith labours at the Ministry of Truth revising history to square it with the Party’s ever-changing reality, but it is his lover Julia’s work in the Ministry’s fiction department that struck me this time around. Her job, she tells Winston, is working the “novel-writing machines,” which consists of “chiefly in running and servicing a powerful but tricky electric motor.” She off-handedly refers to these machines as “kaleidoscopes.” Asked by Winston what the books she produces are like, she replies, “Oh, ghastly rubbish. They’re boring, really. They only have six plots, but they swap them round a bit.” These novels function as a societal soporific, titillating the masses with stories by turns smutty and thrilling, but which deaden their readership by circumscribing what is possible to imagine.

Julia’s description struck me as uncannily prescient, conceiving as it did a sort of difference engine version of Chat GPT. The point of Julia’s work is the same as that of Newspeak, the language replacing English in Orwell’s dystopian future. Newspeak radically reduces available vocabularies, cutting back the words at one’s disposal to a bare minimum. In doing so it curtails, dramatically, what can be said and therefore what can be thought—eliminating the possibilities for resistance by eliminating the ability to articulate resistance. How does one foment revolution when one lacks a word for revolution?

I’m banning AI, insofar as I can, because its use cranks the law of diminishing returns up to eleven. In the process, it obviates the most basic benefit and indeed the whole point of studying the humanities, which can’t be reduced to some abstracted skill set. The intrinsic value of the humanities lies in the process of doing—reading, watching, thinking, researching, writing; then being evaluated and challenged to dig deeper, think harder, and going through the process again. There is of course content to be learned, whether it’s the history of colonialism, the Copernican Revolution, the aesthetic innovations of the Renaissance, or dystopian novels like Orwell’s; all of that is valuable because all knowledge is valuable, but inert knowledge is little better than trivia. Making connections, puzzling out knotty and difficult texts, and most importantly making sense of it to yourself and engaging in dialogue about it with others—it is this process wherein lies the great intangible benefits of the humanities. The use of AI is kaleidoscopic in the sense Julia alludes to in 1984, providing the illusion of variation and newness, but ultimately just a set of mirrors combining and recombining the same things over and over.